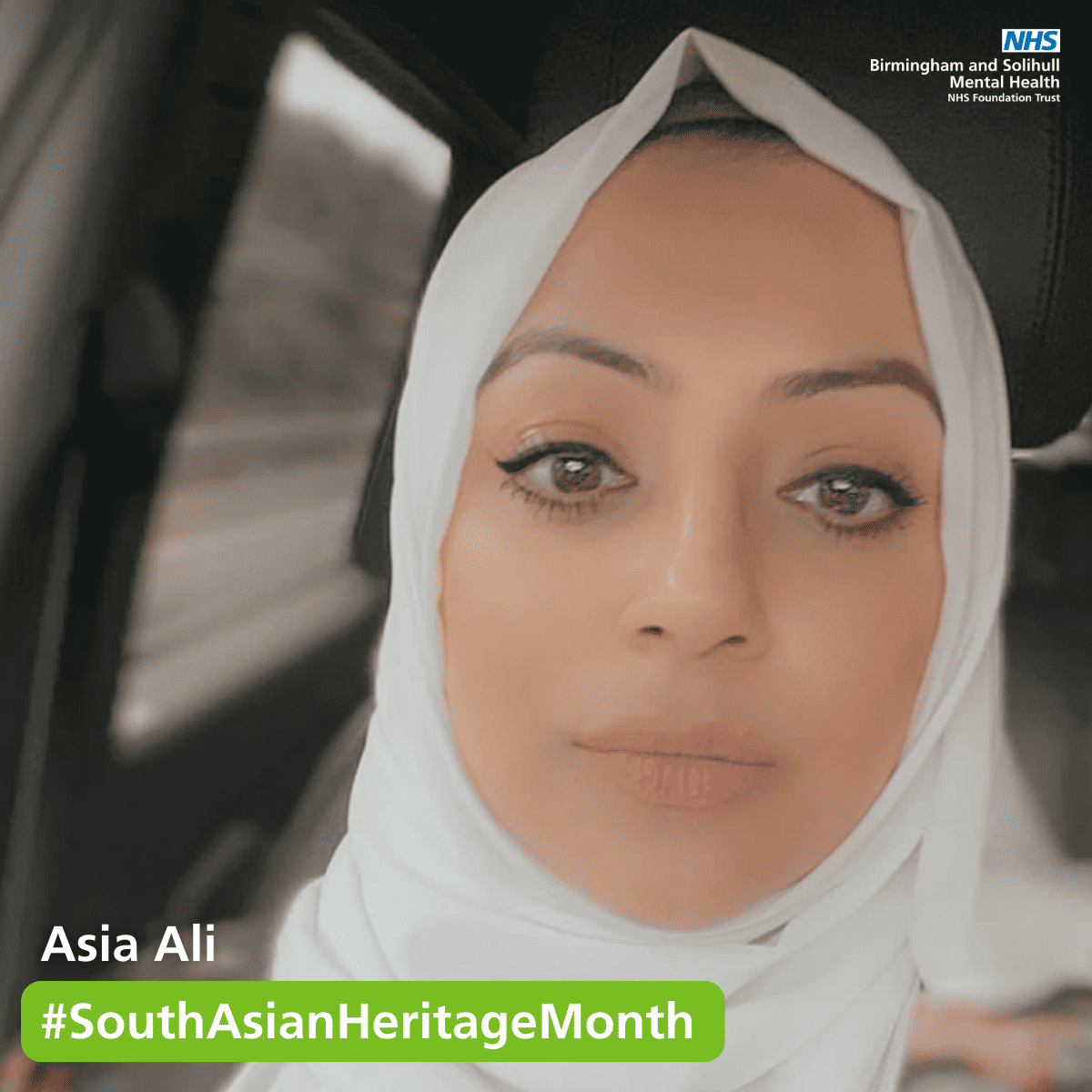

As part of South Asian Heritage Month, we are spotlighting our unsung heroes from across the Trust, today we are celebrating Asia Ali, Peer Support Worker for our Maternal Mental Health Service.

Asia was nominated by Samantha Day. Samantha said:

“Asia supports women, and their families who have experienced perinatal loss or are pregnant following perinatal loss. She connects with women from the South Asian community, speaking Urdu and understanding some of the stigmas and barriers to accessing support. She also runs a drop-in group for women who have been impacted by perinatal loss and encourages conversation and education through promotion, training and talking on the local radio. She is very passionate about making the service equitable and accessible to all communities and ensuring that the voices of servicer users are heard.”

We touched base with Asia for her to tell us a little bit more about what life was like growing up in a British Pakistani household, and how it has shaped her into the woman she is today, here is what she said:

“I was born in Birmingham City Hospital and raised as here as a British Pakistani. Both my parents arrived in the UK as migrants in the 1970s. I would say my childhood was an amalgamation of rich diverse culture, growing up amongst neighbours from Ireland and Jamaica gave me an insight on the similarities we shared. The days of unity and security within the community, where doors weren’t locked, and neighbours could pop in with homemade delicacies to share along with compassion, time, and a sense of camaraderie in the air.”

How they all awed at my mother’s henna, dyed hair flowing down to her hips in vibrant red, sharing our cultural traditions was such a norm.

“My both parents were born in Pakistan. My father was in the Pakistani Army, and he was selected among the few offered the chance to migrate to the UK. My parents had three daughters already in Pakistan. They were much older than me and it often felt that they had more in common to those belonging to a different generation to me. As the youngest of four daughters, I was born in the UK. I was born weighing 2.5lbs with a less chance of survival kept in an incubator for almost two months.”

“Growing up as a child, I was often told that I was ‘a miracle baby’. My father was very regimented in his daily life, and this reflected in his thought process. He believed in home schooling, however despite this my father gave consent to me attending the local primary school. To my sisters, this decision may have displayed a slight hint of favouritism towards me. Their parenting style differed immensely from my sisters to me. My sisters were raised in a very strict disciplined environment. Being girls, this may have been a great influence on how they were parented.”

“Secondary school admissions were upon us, my father’s cultural insecurities did not allow him to send his youngest out in the big bad world. The battle began. I was adamant I wanted to attend school and get an education; this tug of psychological war of back and forth went on for a year. Due to this, I was absent on many occasions, I missed out on what is called year seven now. Finally, my father agreed that I attended a girls only school. Gaining my father’s trust was a privilege, a huge development as I needed his approval. It was not an easy task to create that balance between the generational mindsets.”

“I found the school years quite challenging in terms of ‘fitting in’. I was not allowed to wear western clothes; I was always fully covered and in traditional shalwar kameez (loose tunic and trousers). Non uniform days were a challenge, my teenage hormones wanted to look cool and pretty with makeup like the other girls and fit in. My father did not approve of this as it went against what he believed in. For my father, it was not culturally acceptable to not wear traditional clothing. There were fears of me rebelling against my father’s beliefs and values of what is acceptable. This created an identity crisis for me, was I British or Pakistani…?”

“An important trip to Pakistan was quite enlightening as I was taught to uphold family values and maintain family ties. This was a crucial aspect of my upbringing. These trips taught me etiquettes, cultural differences, values, language barriers as I spoke mainly English with a very broken Urdu dialect. I was a well-behaved obedient child growing up and often found myself struggling to find a medium between being a UK born Pakistani and just a British born. I often found myself a mediator to my father explaining everything, whether that was between a teacher or some other professional where there was a lack of awareness and understanding. Growing up as a first-generation born and raised in the UK posed many challenges.”

“My mother used to teach Arabic to the local children. Every Thursday, she would make a huge dish of sweet rice and distribute to all the neighbours on the cul-de-sac. This was also a Pakistani value, hospitality. It brought everyone together, people were not concerned by the language barriers, my mother spoke very little English, yet the language of food, hospitality and community was always understood by everyone. My childhood was filled with experiences of diverse communities came together. Skin colour, language, dialects, places of origin created no barriers to community and connection. This was the true meaning of being a British Pakistani, a place of diversity and acceptance. I do feel privileged and very blessed to have had a rich childhood and experienced the safety of children playing outside with no fear, where there was love and compassion among neighbours, where race, colour and culture did not come in the way.”

Published: 27 July 2023